What We Do

The Firefly Group helps people use everyday situations for learning and connecting to the Big Picture. After working with Firefly, you will be energized with specific action steps to achieve your goals.

We do this through training of trainers, leadership development, performance improvement training, strategic planning, and clarification of organizational mission and vision. Our methods are engaging, thought-filled, and results-oriented.

If

this sounds like a good direction for your organization, let's talk about

how we might collaborate! Please give me a call (802.257.7247) or send an

. - Brian

If

this sounds like a good direction for your organization, let's talk about

how we might collaborate! Please give me a call (802.257.7247) or send an

. - Brian

Your ETR (Estimated Time to Read): 20 minutes Your ETII (Estimated Time to Implement Ideas): 8 weeks |

Boredom Busters

Boosting Engagement in Meetings, Classrooms, and TrainingsDate: Monday, September 23, 2013

Time: 9:00 - 3:00; 8:30 Registration

Place: Chelmsford, MA

Cost: $295

Tired of being tired in meetings, trainings, and at work? Plan to attend this workshop offered by Brian Remer. Gain practical insights about motivation and learn techniques you can use tomorrow to increase commitment in the workplace.

Read the details and register HERE.

August 2013

|

Say

It Quick |

Discoveries bits of serendipity to inspire and motivate |

Ideas fuel for your own continuous learning |

Activities tips and tricks you can try today |

| Deliver the Message | 8 Steps of Design | The 4-A Model |

Many subtle messages are included in the training we design and deliver. Learn about these indirect communications beginning with this story in exactly 99 words.

Deliver the Message

"Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see." I first encountered this quote by John W. Whitehead on the stationery of a local childcare organization. Whitehead is a noted civil rights lawyer concerned with defending the most vulnerable of our society. His statement highlights the importance of parenting, teaching, and being a good community member.It makes me think: If a picture is worth a thousand words, how many million words is a child worth? We also are all children. What million-word message is each of us delivering right now?

8

Steps of Design

8

Steps of Design

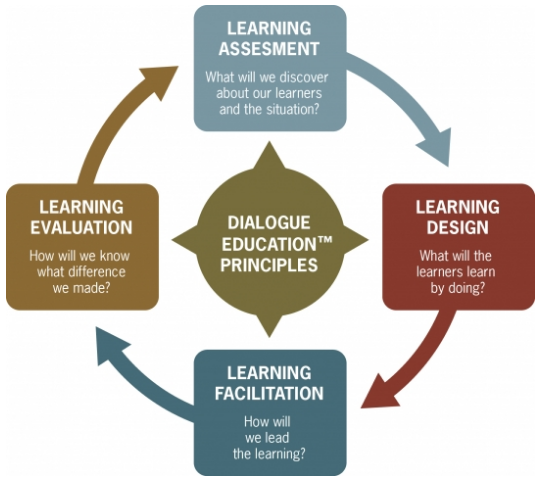

Dialogue Education from Global Learning Partners

The July 2013 News Flash featured two books about training design. Susan Otto and Guila Muir each offer a process and techniques for developing solid learning opportunities. In this issue, we'll take another look at training design from the perspective of the participants and what they actually take away from a workshop and apply on the job.

Dialogue Education is a product of the work of Jane Vella, educator and founder of Global Learning Partners, who has spent her career teaching in Africa, Asia, and North America. She gained expertise in applying the work of theorists such as Paulo Freire, Malcolm Knowles, Kurt Lewin, and Benjamin Bloom. She realized that people learn best when there is an atmosphere of mutual respect and a vigorous dialogue between teachers and learners as well as among learners and their peers.

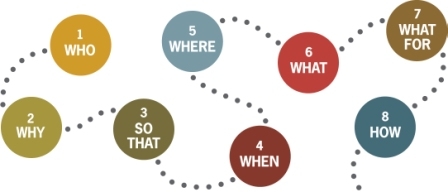

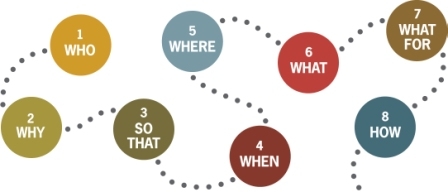

To insure that learning is immediately relevant to participants, Vella recommends a continuous conversation that spans the assessment, design, implementation, and evaluation of a training program. She has summarized this process in her Eight Steps of Design:

1. Who? Describe the participants of the program and who will lead it.

2. Why? Detail the work-world of the participants and its connection to the training topic

3. So That? State what will be different as a result of the training.

4. When? List the date, time, and agenda of the event and determine whether the outcome is realistic.

5. Where? Be specific about the location and environment of the training.

6. What? Outline the specific content of the training.

7. What For? List the specific things learners will do with the information or content to be learned.

8. How? Design the specific tasks and activities that will help people build skills and share their learning.

These eight steps are intended to help planners focus on what the learners will actually need and use. Without considering these steps, planners may become overwhelmed by all the information they want to impart. This can lead to the dumping of massive amounts of information without giving people a chance to build proficiency through practice.

The concepts of Dialogue Education and the 8 Steps of Design provide a wonderful reality check for trainers as well as meeting planners, conference organizers, coaches, and mentors. If you are an educator who realizes that your learners are a "message you are sending to the future," learn more about Dialogue Education HERE or learn about the upcoming International Dialogue Education Institute HERE.

Interview with Global Learning Partners

To understand what makes Dialogue Education different from other approaches to the planning of learning and training events, I invited several members of Global Learning Partners to gather around my virtual coffee table and respond to a few questions. I was joined by Valerie Uccellani, Jeanette Romkema, Michael Culliton, Christine Little, and Joan Dempsey. Here is a short biography for each of them and the result of our conversation. -Brian Remer

Valerie

Uccellani is Owner and Senior Partner of Global Learning Partners. She

is a specialist in designing events and programs for productive and practical

learning and has led a wide range of projects throughout the U.S. and in seventeen

countries of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. She specializes in the areas

of international development, public health, literacy, animal welfare, and

workforce development.

Valerie

Uccellani is Owner and Senior Partner of Global Learning Partners. She

is a specialist in designing events and programs for productive and practical

learning and has led a wide range of projects throughout the U.S. and in seventeen

countries of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. She specializes in the areas

of international development, public health, literacy, animal welfare, and

workforce development.

Jeanette

Romkema is Owner and Senior Partner of Global Learning Partners and a

practitioner of Dialogue Education since 1996. Her areas of greatest depth

include the academic, community development, and voluntary sectors. Particular

areas of interest and expertise are HIV and AIDS, women's health, international

development, the marginalized in society, and the arts. She has extensive

international and cross-cultural experience, having worked and lived more

than 25 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America.

Jeanette

Romkema is Owner and Senior Partner of Global Learning Partners and a

practitioner of Dialogue Education since 1996. Her areas of greatest depth

include the academic, community development, and voluntary sectors. Particular

areas of interest and expertise are HIV and AIDS, women's health, international

development, the marginalized in society, and the arts. She has extensive

international and cross-cultural experience, having worked and lived more

than 25 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America.

Michael

Culliton is a Partner of Global Learning Partners working as an education

and process consultant for organizations that value collaboration and innovative

approaches. He helps design creative and assumption-reshaping projects, meetings,

trainings and events. He has worked in health care and education, with government

and religious institutions, national advocacy groups, human service providers,

international human rights leaders, and values-grounded corporations.

Michael

Culliton is a Partner of Global Learning Partners working as an education

and process consultant for organizations that value collaboration and innovative

approaches. He helps design creative and assumption-reshaping projects, meetings,

trainings and events. He has worked in health care and education, with government

and religious institutions, national advocacy groups, human service providers,

international human rights leaders, and values-grounded corporations.

Christine

Little is a Partner of Global Learning Partners who has combined her skills

in journalism and organizational development. For over 18 years, she has worked

internationally in Latin America using the techniques of Dialogue Education

to help people get the right conversations going so groups align strategy,

processes, and people to create the future they envision.

Christine

Little is a Partner of Global Learning Partners who has combined her skills

in journalism and organizational development. For over 18 years, she has worked

internationally in Latin America using the techniques of Dialogue Education

to help people get the right conversations going so groups align strategy,

processes, and people to create the future they envision.

Joan

Dempsey is Director, Dialogue Education Community for Global Learning

Partners. She holds a master's degree in management from Lesley University

and a BA in philosophy, with a concentration in the Program for the Study

of Faith, Peace, and Justice, from Boston College. For the past eleven years

she has worked in various capacities in the field of animal protection and

before that was active in the anti-nuclear peace movement.

Joan

Dempsey is Director, Dialogue Education Community for Global Learning

Partners. She holds a master's degree in management from Lesley University

and a BA in philosophy, with a concentration in the Program for the Study

of Faith, Peace, and Justice, from Boston College. For the past eleven years

she has worked in various capacities in the field of animal protection and

before that was active in the anti-nuclear peace movement.

Brian Remer: The literature about Dialogue Education emphasizes accountability and effectiveness but these are important for all types of education. Can you expand a bit on those concepts? Who is accountable to whom? How is "effective" defined? What is unique about the way these concepts are approached through Dialogue Education?

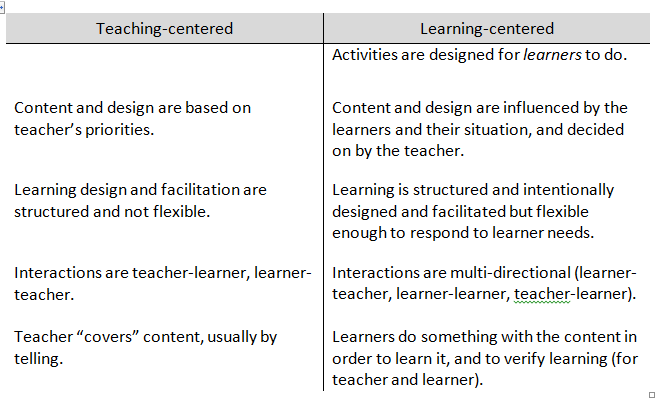

Michael Culliton: Dialogue Education is a learning-centered approach, as opposed to a traditional teaching-centered approach. Some key distinctions are outlined below.

Dialogue Education is effective because learners are able to DO what they are learning. A good example is the four-day Global Learning Partnership foundations course. During the first two days participants learn the theory and experience the approach as modeled by the facilitator. During the last two days, they actually design, teach, and get feedback using the approach.

In the Dialogue Education approach, the teacher is accountable to the learning objectives and for creating and facilitating a design that helps learners accomplish these.

For me, Dialogue Education has been like learning the piano: The first song is not as polished and complex as ones I played later, but it was a song!

The effectiveness is measured in countless stories similar to those that led to the two awards our founder, Jane Vella, received last October for the use of Dialogue Education in a medical school in Chili and for improved child nutrition and mortality in international work. (Our Web site also contains case studies that speak to the effectiveness.)

Valerie Uccellani: Just a few more words about effectiveness and accountability. Many design and teaching approaches focus on objectives and on checking the achievement of those objectives as a measure of effectiveness. But, in Dialogue Education we are rigorous about this. For example, we set objectives that are truly achievable during the learning process itself, and we share responsibility with the learners for checking to what extent that learning really happened. Could we see it? Did we feel it?

We work hard - in dialogue with the learners - to determine what is truly achievable during the learning process, and what isn't. Then, we are jointly responsible for making that learning happen - and for being open to other learning that might emerge which neither teachers nor learners could have predicated beforehand.

Brian: Paulo Freire made the connection that education is political. I am curious about why it might be that this concept has taken hold in developing cultures in a way that it hasn't in our own. It's my perception that, while many people in the developed world understand that "you need a good education to 'get ahead,'" most people do not realize that the way we learn can be used to keep employees in their place or to control children in school. Why is it we are not making those broader connections to work and relationships?

Michael Culliton: This is such an insightful and profound question. However, I cannot answer the "why." (I am personally fascinated by the persistence of what many organizational development people call the "command and control" approach to management and training.) Much of organizational life in the West seems dominated by a management and education style akin to a military model. For me, this Dialogue Education is an antidote.

Valerie Uccellani: Brian, just from your question I can tell you would love Dialogue Education. Why? Because you are aware of what we know to be true: education in all its forms is political. It is evident in the kindergarten class and in the public charter school that my daughter attends. I sat in that classroom as a quiet observer nearly jumping out of my seat, because I could see how the teacher, through her closed questions (outlined in her state-mandated curriculum) essentially "told" students what they should believe about war.

From my years of Dialogue Education work, I could easily see an alternative approach through which some essential, and valuable information from the curriculum would have been provided to the students, combined with a few truly open questions that invited their own thoughts about war. In fact, many children had their hands waving in the air, wanting to share their thoughts but they never got the chance.

I've worked in 18 different countries over 30 years. This scene is one I've lived in many training rooms of many organizations and in many workshops in many communities. It's insidious. We pretend to ask questions but really we are telling people to think like us. We don't want to hear information or perspectives that counter ours because that would shake our world.

So, yes, education is controlling. And, yes, dialogue education is a sincere effort to undo that. Thus our tagline: Revolutionize your learning, transform your world.

Christine Little: I am not sure that I agree that it has taken hold in developing cultures more than in our own. Patriarchy is a strong model and powerful influence over the way we operate in institutions all over the world. It is persistent because it feels safer for everyone and because we have embedded that model into our systems, and even into our own psyches. We look to our teachers to tell us how to think and what to believe. We look to our bosses to tell us what to do and how to do it. We look to our politicians to solve our problems. We resist when they push that responsibility back on us. We penalize teachers, bosses and politicians when they admit they don't know. We set systems up to reinforce this paradigm - grades, demerits, performance reviews, poll numbers.

And yet! In many institutions, groups, and communities, there are pockets where people are experimenting with a new kind of paradigm. This is our choice, each and every time we enter a room with a group, whether we are the teacher, or the student, the leader, or the team member, the politician, or the citizen.

Brian: Having a dialogue between educators and learners implies equality between the two. Yet there are always differences of power between teachers and learners. How do you reconcile that? For me, being in dialogue means I recognize the need to listen, I expect to find value, meaning, or worth in what I hear, and I plan to change my actions based on what I learn. What I am curious about is how one gets to that place where one is ready and willing to have that kind of dialogue?

Michael Culliton: In Dialogue Education I think we see all involved as "learners"-the participants and the teacher. During a given learning event, we do assume temporary and distinct roles.

Those assuming the role of teacher are accountable-in dialogue with the participants-for selecting relevant content, designing learning tasks that have people doing something meaningful with the content, and then facilitating the learning event in a way that invites and respects the experience and wisdom that each learner already brings to the content while meeting the learning objectives.

As you astutely observe, in this approach the teacher needs to listen to learners and their experience and then use this to shape the content and process in ways that will maximize the learning.

Valerie Uccellani: Thank you, Brian, for the chance to speak to this because, as Michael said, the roles are distinct and we must recognize that.

When I'm in the role of teacher (and it's why we intentionally use that word), I do indeed have skills, information, experience, insights around a topic that most learners in the room will not have. I want to embrace that difference and live up to it. I want to work hard to figure out what I can offer the group that might be relevant and immediately applicable for them. [Otherwise adults won't want it.]

But, being a teacher doesn't give me the right to be manipulative or superior or to dismiss what the learners bring. It is simply to recognize that I have something that might be of value to them, and they have something (complementary skills, information, experience, and insights) that will be valuable to the group. I design for all of that to come forth.

Christine Little: In a teaching environment, what I know, my expertise, is one valuable resource of many in the process of learning. It is important to own that, as teachers. We can go to the other extreme of being stingy with that, and the results are not good. But it is only one valuable resource. The other resources include the learners' experience, context knowledge and real lives. They are the experts on that. So, if my teaching is about leading change in an organization, I will bring some useful processes, some interesting research, or some core values. The people who come will bring a clear picture of their own situation, and their stories, what they have tried, what has worked, what has not worked for them, etc. Their stories may be the element that actually stimulates a colleague to try it out.

Brian: What suggestions do you have to help facilitators maintain an attitude of dialogue and not slip into old patterns or hierarchical relationships? I use facilitator to describe the person who offers a process, a question, or a technique that will provide the "just right challenge" so people can accomplish the hard work of learning. Is there a tip, attitude, or frame of mind that you can suggest?

Michael Culliton: Jane Vella, the founder of Global Learning Partners, offers an anecdote that summarizes this for me. A man in New York hails a taxi. When the taxi pulls over, the man opens the door and asks the driver, "Say, how do I get to Carnegie Hall?" The driver replies, "Practice. Practice. Practice."

When I took my first course in this approach, on day three I found myself feeling depressed because I realized that although I had been committed and talking about so many of the principles behind this approach, I was awful at practicing them. It's easy to say, "Oh, yes, it's important to respect the learner. Yes, we must design a session so that people can actually engage with each other about the content and then actually do something with it before they leave." It's quite another thing to actually do it.

Over and over again, I have been in conversations with people who agree with the principles and practices we employ in this approach: respect, engagement, transparency, dialogue, etc. However, like me, it is another thing when they go to teach: there is often faint evidence of these principles in practice, and the learning suffers as a result.

In this approach we design learning tasks: a written, clear activity for the learners with all the resources they need to complete it. If we design well, during each task, our role as teachers is to set the task and then get out of the way, being available as a resource as the people engage with the content.

Jeanette Romkema: Here are a few tips:

Brian: If an employer says, "I want my employees to know X," or if a school board says, "We need students to attain a proficiency of Y in math," how do you reconcile that with a dialogue approach?

Michael Culliton: I would turn the question around. How can you help people learn well without being in dialogue with them?

A teacher or trainer can gain so much from inviting and being curious about how a learner is understanding content, especially a learner who may be struggling with a concept. This is as true in math or science as it is in art or communications.

In the traditional approach we often confine our responsibility as teacher to "delivering the content." We think, "Okay, I've told the learners about it. Now it's up to them: sink or swim." In the Dialogue Education approach, the teacher is accountable to the learning. We observe: "Can the learner do what she is learning?" If not, then we need to be in dialogue, to understand how she is thinking about the content; to offer additional tasks that lead to success in the doing.

Christine Little: If an employer says I want my employees to know X. I say. Great! Why? What's going on that tells you your employees need to know X? That is the beginning of a dialogue. It can grow from there.

Brian: What reactions do you get from clients when you ask to include learners in the design of a meeting or training?

Michael Culliton: We don't typically design with learners, but we do seek important input and information to inform a design.

We all seem so pressed for time these days that there are often questions or some resistance to this stage, which we call a Learning Needs and Resources Assessment. However, all of us have been to THAT training or workshop where we spent a day in a course we could have taught or perhaps in a class that started way above our heads.

In this approach we talk to people up front so that we get a clear sense of what they already know about the content and to get their feedback on the proposed learning objectives. This pre-session dialogue is invaluable to the design stage.

Brian: Many times one doesn't have the luxury of access to participants and end users during the design process. What then? In other words, how, with whom, and when does dialogue inform the design of a learning event?

Michael Culliton: Honestly, with technology these days, we can usually be in dialogue with learners in some way before we design. The "luxury" mentioned sometimes has to do with time.

If an organization totally resists this idea-and this occasionally happens-then it becomes clear that the Dialogue Education approach is really not compatible with the culture of the place.

Valerie Uccellani: You know, that's a great point. A dialogue-based approach to collective learning has to be in line with the culture of a place. For example, if the place wants a training "tomorrow" and doesn't have time to invest in examining fundamental questions beforehand, then this approach is not for them. If an organization wants to create learning materials for the community around a topic, but doesn't have a deep understanding of that community, and doesn't allow me to work directly with people who do, then this approach is not for them.

Like Michael said, it doesn't need to be a huge investment of time. For example, if we are creating a workshop for staff of an organization, a simple (optional) survey and a few telephone calls might be enough. But, if we are going to create something of lasting value (like a set of story-based materials for national use around HIV prevention, or a personal finance package for low income families throughout New York City), then we'll need to invest our time and energy in understanding what will really make a difference.

Christine Little: There are so many ways to do some exploration before you design. It always pays off. It is like designing anything. It is expensive to trot out a new shopping cart design, only to discover that it doesn't work for shoppers! Same thing with a learning event. If you can't talk with everyone, can you talk with a sample, if you can't do that, what could you do to get a clearer picture of who they are and their unique situation? A colleague who was designing a learning program about nutrition said she gained her best insights by going shopping with food stamps.

Brian:

The eight questions that you pose in order to design a training or meeting

have me a little confused. Number 2, Why, seems a lot like number 7, What

for, and number 6, What, is similar to number 8, How. What can I do to keep

this all straight? Do the steps of design need to be followed in order? What

flexibility is possible in using them?

Brian:

The eight questions that you pose in order to design a training or meeting

have me a little confused. Number 2, Why, seems a lot like number 7, What

for, and number 6, What, is similar to number 8, How. What can I do to keep

this all straight? Do the steps of design need to be followed in order? What

flexibility is possible in using them?

Jeanette Romkema: I know what you mean. I think the attempt to simplify the steps to "W" words has not always served us. I find it easier to talk about and use this language:

Michael Culliton: The Eight Steps of Design are a discipline: for most of us, we are thinking about all these questions as we plan and design. So we might be taking notes on all these as we engage in a planning conversation. The discipline comes in backing up and making sure we have really done each step.

For some practitioners, there are three foundational questions and steps that get primary focus up front:

The answers to these three questions profoundly influence the remaining steps.

We have some great templates for these planning steps on our website so that you don't have to work hard to keep them all straight.

Valerie Uccellan: Brian, the first thing I'd like to share is that these steps all influence each other in such a way that when you change one, you might change any of the others. So, yes, they are more of a collective description of what you are planning then a series of questions you answer in some set order.

For example, I'm using these steps now to think through the design of a counseling approach to be used in a workforce development program. We are thinking through the people (the clients, the counselors), the purpose (why have counseling as part of this program at all?), the intended change (what do we expect clients will gain from these counseling relationships?), the place and time (where should counseling happen, at what point in the program and with what frequency?), the content (what skills or information will counselors be prepared to address with clients?), objectives (what do we expect clients to actually do and accomplish during the counseling sessions?), and process (what counseling processes and materials would make most sense for what we've laid out above?). You can see that:

Without this

"discipline," as Michael so smartly calls it, organizations tend to invest

lots of time and money in processes that don't fit the people, the purpose,

the time, or the change they want to see. These steps protect us from making

that costly mistake.

Brian: How does the Dialogue Education design process compare to ADDIE (which also began in the 70's) and Agile design techniques which are currently emerging?

Valerie Uccellani: Not too long ago, Global Learning Partners worked with DynaMind (a superb international e-learning firm) to craft a proposal for UNICEF. The request for proposal required that we lay out our approach using the ADDIE model. I loved it. It was quite in line with our framework. Here are a few things I like about this model:

Our principles-to-practice framework deepens the ADDIE model in a few ways. For example, per our description of the project above, our model demands that assessment is focused not only on needs but very much on resources brought by teachers and learners. Furthermore, it demands that the assessment phase is ongoing - we are continually looking to learn more about the people, the situation, and the realistic, desired change so that we can design with this in mind, and adjust our design in a responsive, flexible way.

One additional strength of the Principles to Practices Framework is that the evaluation phase is seen as something that overlaps with the phases before and after it: during implementation, we are all looking for evidence of learning, and asking learners to name ways in which they foresee transferring that learning into their realities (in ways that we, as designers could not predict or prescribe.) This creates a new situation for us to continually assess.

Principles to Practice Framework

Brian: Which professionals most use Dialogue Education?

Joan Dempsey: Dialogue Education attracts many professional trainers, project managers, and department heads from what I think of as mission-driven organizations, whether they're for profit, non-profit, government, or academic. If a person is trying to advance his or her mission in the world by teaching others on their staff or in the field, Dialogue Education is for them! You can find a list of our clients HERE.

Jeanette Romkema: It is true that Dialogue Education is helpful to all and any professional, many of which Joan mentions. I feel it is also important to mention that Dialogue Education is congruent and helpful to a wonderful variety of practitioners within the field of education as well. Some of these are people who teach and practice:

Brian: I don't hear of Dialogue Education being used in business and public education. Am I out of the loop or is there some reason it has yet to catch on in those professions?

Joan Dempsey: You're not entirely out of the loop, no. The Dialogue Education work we've done over the years has primarily come to Global Learning Partners via word-of-mouth recommendations from satisfied clients, and as a result our clients have tended to come from civil society and international development, faith-based, public health, and higher education organizations. That said, we've done work with for-profit businesses and public education programs, too, and would love to do more in those sectors. Some of our graduates are out there working in those sectors, introducing them to Dialogue Education. The beauty of Dialogue Education is that it's applicable anywhere, and we aim to spread the good word as broadly as we can.

Jeanette Romkema: I love working with clients from these two areas: Dialogue Education in the business sector offers more humane respectful ways of operating while still having 'profit' as a goal; and, Dialogue Education in the public education sector offers ways to ensure meaningful and relevant learning which results in higher grades and a love of learning - now won't that be a wonderful change from what we often see.

Brian: What are your favorite techniques for maintaining an attitude of dialogue during a training?

Valerie Uccellani: Good question because people often ask us for techniques, and we've got them. In fact we have many free resources on our website such as our Ten Tips sheets that speak directly to this question. Some of my favorite techniques for ensuring dialogue are:

Having said all that, I'll say what any of our Dialogue Education practitioners, worldwide, would say: It is not so much the techniques we use, but, rather our intent for dialogue that makes a difference.

Christine Little: Here are some very practical things that I have taken from Dialogue Education that have become central to my way of working:

The

4-A Model

The

4-A Model

Joan Dempsey of Global Learning Partners has offered this activity for people who want to apply some of Dialogue Education techniques. Joan writes:

Here's one of the best tools out there for designing learning tasks. Readers can take this approach and apply it to any learning task they'd like to create, which means this is more relevant than if I'd chosen a favorite learning task of my own that wouldn't be applicable to more than a handful of readers.

We call this tool the 4-A Model: ANCHOR, ADD, APPLY, AWAY. Here's a summary:

Read more and study examples of the 4-A Model HERE. Discover an enormous library of facilitator tip sheets HERE. If you use any of the concepts, tips, or techniques of Dialogue Education, please so we can keep our own dialogue of learning flowing.

|

Whether you need a keynote speaker, or help with strategic planning, performance improvement, or training facilitators and trainers in your organization, I look forward to your call (802.257.7247) or . -- Brian |

Read previous

issues. Click Library!

To add or delete your name to our mailing list, email

with a short note in the subject line.

I want this newsletter to be practical, succinct, and thoughtful. If you have suggestions about how I can meet these criteria, please let me know! Send me an with your thoughts and ideas.

Home

| Services

| Products

| Mission

| Ideas |

The Group

| The Buzz

(c)

2013 The Firefly Group